Money’s evolution reflects humanity’s pursuit of seamless exchange, enabling the smooth flow of goods and services across individuals and organisations.

From the straightforward barter system to the complexities of our modern financial landscape, money demonstrates its adaptability and innovation.

In a world that is constantly changing, our use and understanding of money evolve hand in hand.

The Barter System:

In the early stages of human economic interactions, the barter system served as a straightforward method of exchange. People engaged in direct swaps of goods and services based on their individual needs and perceptions of value. The simplicity of the barter system allowed individuals to trade items they possessed for items they desired, fostering early economic transactions.

It is nice and simple but the simplicity is also why it does not work.

Imagine you are a farmer who specialises in growing apples, and you have a surplus of apples. Meanwhile, there’s another farmer nearby who specialises in cultivating oranges. You have a craving for oranges and would like to obtain some.

You might think this is easy, we can discuss the quantity and quality of the apples and oranges, and we will be able to agree on a fair exchange rate of my apples for his oranges.

But what happens if the orange farmer does not like apples?.

In the barter system there needs to be a “double coincidence of wants”, both people must want what the other person has. In this case the orange farmer does not want apples, they may want bananas. The Apple farmer will need to try and see if he can swap his apples for bananas, so that he can swap those for the oranges.

If people do not have the desire for what you have, or values it differently to you things start to get a lot more complicated fast.

Ok let’s look at another complication, that orange farmer is willing to trade his oranges for apples, but the oranges are not in season yet, so he does not have anything at the moment to trade but will in the future.

What happens here, The apple farmer and the orange farmer can agree on a future exchange, acknowledging that the oranges are not available at the moment but will be in season later.

The apple farmer, in essence, provides the oranges on credit, accepting the apples in the present with the expectation of receiving the oranges in the future when they are available.

The parties involved would need to establish clear terms and conditions for the future exchange. This may include specifying the quantity and quality of oranges to be provided, as well as the timing of the exchange. Such arrangements rely heavily on trust between the parties. The apple farmer trusts that the orange farmer will uphold their end of the agreement when the oranges are in season.

As we can see while the barter system is simple and works, as societies grew more complex, and the range of goods and services expanded, the barter system became increasingly impractical.

This leads to Commodity Money.

Commodity Money:

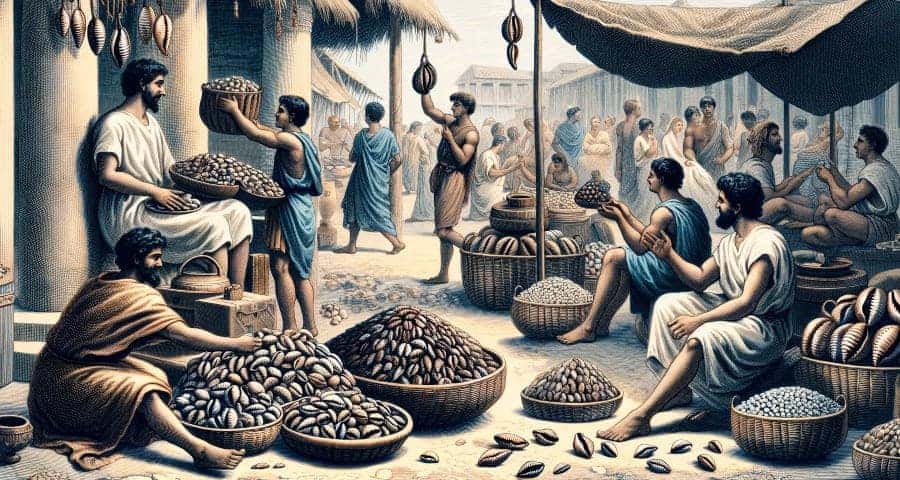

In a barter system, we directly trade goods or services we have for those we desire from others. But given the limitation with the barter system, what if instead of trading directly one for one we trade for something that we use as an intermediary(Commodity) that has value and other people will want.

Let’s say you have a flock of sheep and now you want a cow. Trading directly does not make sense as they are unlikely to have equal value and you can not split it up to make it of equal value, but if we introduce a commodity with inherent value, we could use that to serve as a universally accepted medium of exchange.

One of the early commodities that was used for this purpose was cowrie shells.

Cowrie shells, like other commodity money, possessed intrinsic value beyond their use in transactions. They were valued for their aesthetics, rarity, and cultural significance.

Cowrie shells became a standardised unit of value within a community, enabling individuals to assess the worth of various goods and services in relation to these shells.

Cowrie shells served as a versatile medium of exchange, overcoming the challenges of direct barter. Individuals could trade goods and services for cowrie shells and, in turn, use the shells to acquire other desired items.

Due to their portability, durability, and cultural significance, cowrie shells gained widespread acceptance. They were recognized across communities, making them a universally accepted form of commodity money.

Going back to the example where someone with a flock of sheep wishes to acquire a cow. Instead of negotiating a direct swap, the parties involved might agree to use cowrie shells as an intermediary. The owner of the sheep could trade a certain quantity of sheep for an agreed-upon amount of cowrie shells, and then use those shells to acquire a cow from that person or a completely new individual to trade those cowrie shells for the cow.

With cowrie shells being a durable and widely accepted commodity, that could be stored over time without the risk of spoilage or depreciation, as intermediary commodity brought about several significant benefits:

Standardisation of Value: Switching to a commodity as an intermediary, such as cowrie shells, provided a standardised unit of value that simplified the process of assessing and comparing the worth of various goods and services. By assigning a specific price in cowrie shells to each item, individuals could easily gauge the relative value of different commodities within the community.

Facilitation of Comparisons: This standardised pricing system enabled individuals to compare the values of diverse goods and services directly. For instance, if a cow was priced at a certain number of cowrie shells and a sheep at a different amount, people could make informed decisions about their trades. This facilitated a more transparent and efficient marketplace where individuals could evaluate the relative value of different items based on their established cowrie shell prices.

Enhanced Economic Planning: With a standardised unit of value, individuals could engage in more strategic economic planning. Farmers, herders, and traders could calculate the expected returns on their goods or services, making it easier to make decisions about production, trade, and investment. This level of predictability and transparency contributed to the overall efficiency of economic transactions.

Reduced Ambiguity and Disputes: The use of a standardised commodity as an intermediary reduced ambiguity in transactions. Clear prices in cowrie shells provided a common language for trade, minimising misunderstandings and disputes over the value of exchanged goods. This transparency contributed to a more harmonious and reliable economic system.

Future Transactions: Individuals could store value in the form of cowrie shells and use them in the future to facilitate transactions when the need arose. This allowed for greater flexibility and planning in economic activities.

Risk Mitigation: Storing value in a durable and stable commodity helped mitigate the risks associated with perishable or fluctuating goods. Unlike perishable items, cowrie shells maintained their value over time, providing a reliable store of wealth.

Medium for Savings: Commodity money, acting as a medium for storing value, served as an early form of savings. It allowed individuals to accumulate wealth and make strategic decisions about when and how to use that accumulated value.

Inter-Community Transactions: The ability to store value in a standardised form also facilitated transactions between different communities. Cowrie shells, with their recognized value, could be easily transported and used for trade in diverse regions.

Precious metals:

The shift from commodities like cowrie shells to precious metals as a medium of exchange marked a significant evolution in the history of money. This shift was influenced by various reasons including the desire for more durable and widely accepted forms of currency.

The key elements of this transition:

Durability and Portability: While cowrie shells served as an effective medium of exchange, they had limitations in terms of durability. Precious metals, such as gold and silver, were highly durable and resistant to wear and tear. This durability made them more suitable for use as a long-term store of value and a medium of exchange.

Intrinsic Value: Precious metals have intrinsic value due to their rarity and unique properties. Unlike cowrie shells, which were valued for cultural significance and aesthetics, precious metals were universally recognized for their scarcity and desirability. This intrinsic value contributed to the stability and trustworthiness of these metals as a medium of exchange.

Divisibility and Uniformity: Precious metals could be easily divided into smaller units without losing their intrinsic value. This divisibility addressed one of the challenges of direct barter and facilitated transactions of various sizes.

Widely Accepted Standard: Over time, societies recognized the advantages of using precious metals as a standardised unit of value. Gold and silver became widely accepted as a medium of exchange not only within local communities but also in other regions and international trade. This wide acceptance contributed to the emergence of a more interconnected and efficient global economy.

The Rise of Coins:

While the use of precious metals marked a significant advancement in trade, the inherent challenge of accurately weighing raw gold or silver ingots posed practical difficulties, especially in smaller transactions where precision in determining value was crucial.

Raw gold and silver, often in the form of ingots or nuggets, lacked standardised weights, each piece varying in weight and value. This variability complicated the process of reaching a mutual agreement on the value of these raw materials.

For everyday transactions involving goods and services of varying values, the introduction of standardised units of measurement became essential. Coins emerged as a practical solution by offering consistent weights and denominations, providing a universally recognized and accepted value for each coin. This standardisation simplified transactions, fostering a more efficient and reliable medium of exchange.

Coins offered the additional advantage of easy divisibility into smaller units without compromising their value. This flexibility was crucial for facilitating transactions of varying sizes, from minor daily purchases to more substantial trade deals.

Portability became another significant benefit of coins over raw gold or silver ingots. Coins, being more compact and lightweight, enhanced trade by allowing individuals to carry significant value conveniently.

Issued by rulers, governments, or mints, coins often bore stamps or inscriptions of the issuing authority. This symbol of authority not only reinforced the authenticity of the coin but also provided a tangible link to the backing of the issuing entity.

Beyond their utilitarian function, coins served as a means of showcasing authority and sovereignty. The practice of stamping the faces or symbols of rulers on coins asserted the identity and pride of the issuing entity, contributing to the overall trust in the monetary system.

The specific markings and features on coins also played a crucial role in authentication, reducing the risk of counterfeit or debased currency. This contributed to building trust in the reliability of the coinage system.

Paper Money and the rise of banks:

Carrying large quantities of coins, especially in precious metals like gold and silver, was cumbersome and posed security risks, making individuals vulnerable targets. Goldsmiths, skilled craftsmen in precious metals, emerged as a natural choice for those seeking secure facilities for wealth storage.

Goldsmiths, perceived as trustworthy figures in their communities, established themselves as de facto bankers. They stored valuables for clients and issued credible receipts, laying the foundation for an evolving banking system. Their integration into local communities enhanced the trust placed in them.

As trade expanded, the need for more convenient transactions arose. Goldsmiths’ certificates, representing deposited valuables, began circulating as early forms of paper money. People found it more convenient to use these certificates for transactions, eliminating the need for physical transfer of precious metals.

The rise of banks followed, marked by innovation and competition. Banks, rooted in local communities, offered various financial services. Fractional reserve banking emerged, allowing banks to lend a portion of deposited funds. Each bank had the flexibility to set interest rates, lending policies, and terms, adapting to local needs.

However, this proliferation of banks led to challenges. A lack of standardisation in banking practices created confusion, with currencies from different banks facing varying levels of acceptance and trust. The variety of currencies complicated transactions, especially in regions with multiple banks operating independently.

Furthermore, the rise of banks introduced an element of trust that wasn’t present when it was just commodity money. In commodity money systems, the value is derived from the inherent value of the physical object (e.g., gold or silver). Representative money, on the other hand, relies on trust in the issuing authority that promises to redeem the money for a commodity. This introduces an element of vulnerability if trust in the issuing entity is eroded.

Rise of the U.S. Dollar

With the implementation of the Coinage Act of 1792, the fledgling United States government stepped into the realm of currency production, establishing the U.S. Mint and taking control of coinage regulations.

Recognizing the imperative for a consistent and reliable currency system to facilitate domestic and international trade, the Act formally designated the U.S. dollar as the standard unit of money. Each coin contained specified amounts of silver and gold.

Although the coins derived value from the precious metals they contained, providing them with an inherent floor value, their assigned value was a government decree rather than being based on the market value of the metals. This introduced a currency system positioned between contemporary fiat currency and commodity currency.

To uphold uniformity and deter counterfeiting, the legislation meticulously detailed specifications for various coins, encompassing their sizes, weights, and designs. This standardisation not only preserved the integrity of the coinage system but also instilled confidence in the currency.

The Act introduced an array of coin denominations, spanning from cents and half dimes to dimes, quarters, half dollars, and dollars, each possessing distinctive specifications and metal compositions.

By stipulating the metal composition of each coin, predominantly utilising gold and silver, the Act aimed to convey a sense of stability and reliability to the public.

Additionally, the legislation mandated specific designs for the coins, featuring images of prominent figures such as Lady Liberty, enriching the aesthetic and symbolic dimensions of the currency.

Recognizing the peril of counterfeiting, the Act imposed penalties on those attempting to produce counterfeit coins, establishing legal consequences for individuals engaged in such activities. This further fortified the integrity of the newly instituted U.S. currency.

As the value of the currency was not directly tied to the precious metals it contained, but rather dictated by government decree, the Coinage Act of 1834 became necessary to adjust the weight and metal content of certain U.S. coins. This was particularly pertinent for gold coins, as the value of gold had surged beyond the face value of the coin, prompting a need to reduce the amount of gold to ensure that the commodity value did not surpass the face value.

The Rise of Paper Money:

During the Civil War, the Union government confronted substantial financial demands to fund military operations, triggering the need for a financial solution that didn’t rely on acquiring more precious metals.

The Legal Tender Act of 1863 was enacted to address this fiscal challenge by authorising the issuance of paper currency, famously known as “greenbacks.” While this move allowed the government to finance its activities, it marked a significant departure from the established norm of commodity money backed by tangible assets like gold or silver.

Unlike their precious metal-backed predecessors, greenbacks held no intrinsic value and were not redeemable for gold or silver. This departure raised valid concerns and criticisms, as the government essentially declared these notes as legal tender for all debts, public and private, establishing the foundation for a fiat currency system in the United States.

The shift to fiat currency prompted concerns about the stability of the currency’s value. Unlike commodity money with inherent value, the value of fiat currency relies heavily on public trust in the government’s ability to manage the money supply judiciously.

Critics worried about the potential for inflationary pressures and devaluation when governments possess the authority to create money at will.

While the Legal Tender Act provided the government with the flexibility needed during a time of war, the concerns surrounding fiat currency lingered. The act not only authorised greenbacks but also laid the groundwork for a system of national banks, attempting to bring stability to the nation’s financial system. However, the lingering uncertainties about the risks associated with fiat currency continued to shape public discourse on the nature of money and government authority.

The Federal Reserve System

The United States emerged as a financial frontier marked by minimal oversight, where banks, operating independently under state authority, issued currency, creating a chaotic and unpredictable monetary landscape. The aftermath of the Revolutionary War added to the complexity, burdening the nation with debts and financial challenges.

In response to the financial tumult, Alexander Hamilton proposed a solution, a central bank. The First Bank of the United States was established in 1791, with the aim of managing war debts, building credit, and providing a stable currency. However, concerns over concentrated financial power led to its closure in 1811.

The 1800s witnessed a series of financial panics, from 1837 to 1893, exposing the vulnerabilities of the decentralised banking system to challenges like bank runs and economic downturns.

The turning point came with the Panic of 1907, revealing the inadequacies of the existing system. A failed stock market move and a lack of coordinated money control triggered financial chaos. J.P. Morgan intervened to stabilise the situation, but the need for a more effective system became apparent.

In 1913, the Federal Reserve System was established. Unlike the decentralised past, the Federal Reserve introduced a unified and coordinated approach to managing the money supply and interest rates. Functioning as a central hub, it guides the economy with regional banks collaborating and a central governing board making key decisions. Its crucial role includes stepping in during crises, monitoring the money supply, and assisting the economy in staying on course.

The Federal Reserve is designed to operate independently within the government to make monetary policy decisions based on its dual mandate of maximum employment and stable prices.

The Gold Standard Abandonment

The Great Depression of the 1930s presented unprecedented challenges to the United States and the global economy. In response to this economic turmoil, President Franklin D. Roosevelt initiated a historic move, the abandonment of the gold standard. This pivotal decision, marked by Executive Order 6102 and the Gold Reserve Act of 1934, had far-reaching consequences for the nation’s monetary system, laying the groundwork for a new era in economic policy.

As the Great Depression unfolded, the U.S. grappled with severe deflation, high unemployment, and a banking crisis. To address these economic pressures, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 6102 on April 5, 1933. This bold move aimed to combat challenges by prohibiting U.S. citizens from hoarding gold coins, gold bullion, and gold certificates.

Individuals were mandated to turn in their gold holdings to the Federal Reserve in exchange for U.S. dollars at the prevailing rate. The government’s intention was to increase the money supply, stimulate spending, and counter deflation. However, the immediate impact was a significant departure from the gold-backed currency that had been a cornerstone of the U.S. monetary system.

Building on the foundation laid by Executive Order 6102, the U.S. government enacted the Gold Reserve Act of 1934. This legislation not only formalised the de facto departure from the gold standard but also implemented measures to reshape the monetary landscape.

Key provisions of the Gold Reserve Act included removing gold clauses from contracts, giving the government increased flexibility in managing its finances. This resulted in obligations once tied to gold values being adjusted to the devalued U.S. dollar. The act also empowered the government to modify the gold content of the dollar, facilitating the necessary devaluation to counter deflation and promote economic activity.

The abandonment of the gold standard had profound consequences for the U.S. economy. By severing the link between the U.S. dollar and gold, the government gained more control over monetary policy, allowing increased flexibility in responding to economic challenges. This move set the stage for the eventual transition to a fiat currency system, where the value of money is not tied to physical commodities.

While the decision faced criticism, especially from those who valued the stability of the gold standard, it proved instrumental in navigating the complexities of the Great Depression. The devaluation of the dollar boosted exports, stimulated economic activity, and laid the groundwork for a broader set of economic policies that would define the post-Depression era.

Post War World: The Bretton Woods Agreement of 1944

In the aftermath of World War II, the global economic landscape lay shattered, necessitating a comprehensive framework to rebuild and stabilise international monetary relations. This led to the creation of the historic Bretton Woods Agreement, a landmark accord that not only signalled a departure from the gold standard but also laid the foundation for a new era of international economic cooperation.

During the summer of 1944, representatives from 44 Allied nations convened in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, USA. Their collective goal was to deliberate on the structure of the post-war monetary system, aiming to foster economic stability, facilitate international trade, and prevent the competitive devaluations and protectionist measures that had characterised the challenging interwar period.

The Bretton Woods Agreement achieved a delicate balance between preserving certain elements of the gold standard and introducing much needed flexibility. While gold retained significance, it no longer played the exclusive role it once did. Instead, the U.S. dollar took centre stage.

Under the agreement, the U.S. dollar was pegged to gold, and major currencies were pegged to the dollar. This arrangement established the dollar as the primary reserve currency, leveraging the credibility of the United States’ economic strength and productivity.

The beauty of the Bretton Woods system lay in its unique combination of stability and flexibility. While currencies were pegged to the U.S. dollar, the dollar itself could be exchanged for gold at a fixed rate. This mechanism provided a crucial degree of stability to the international monetary system, mitigating the chaotic fluctuations that had characterised the interwar years.

Additionally, the Bretton Woods Agreement paved the way for the establishment of two pivotal institutions: the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. These institutions were designed to offer financial assistance to countries facing balance of payments problems and to support post-war reconstruction and development projects. They became crucial pillars in maintaining economic stability and fostering international collaboration in the challenging post-war period.

Money is still evolving:

Money remains in a state of constant evolution, continuously adapting to the dynamic needs of societies. The latter half of the 20th century marked a notable shift in banking practices with the introduction of electronic banking, credit cards, and online transactions. Additionally, the concept of money has transcended physical cash, embracing digital forms of currency.

The complexities of the modern world, coupled with the rise of technologies, have introduced new dimensions to financial transactions, providing both convenience and efficiency. From the simplicity of barter to the intricacies of cryptocurrency, money showcases its resilience and adaptability through ongoing transformations.

Looking forward, the journey of money is poised for further innovation. Technologies like blockchain and decentralised finance suggest a future where financial systems may undergo even more profound changes. As we navigate this ever evolving landscape, the essence of trust and confidence remains pivotal, ensuring that money continues to function as a practical tool in our daily lives.